November 20, 2010 marked the 100th anniversary of

the Mexican Revolution that overthrew the Porfirio Díaz

regime (1876-1911). It was the world’s first social

revolution of the 20th century. A century later,

the causes that sparked this popular uprising and gave way

to the revolutionary movement are not only still present,

they are felt even more brutally by the vast majority of

Mexican families. And hunger is the leading cause.

More exclusion,

less democracy

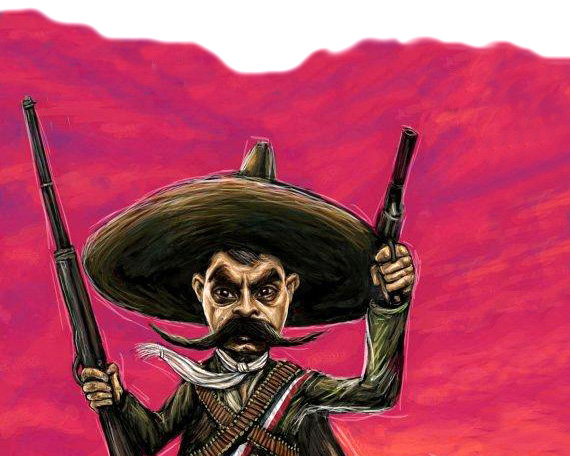

Land! Only land! / The Indians have risen / to recover the

land that the hacendados took from them / Zapata,

leader of southern Mexico / apostle of conviction / was the

voice of the land / their voice of liberation.

(“La

Tierra, Sólo la Tierra” - Revolutionary Corrido, Mexican

folksong)

One hundred years after the Revolution, Mexico is

still a country as rich as it is unjust, with a society

increasingly submerged in poverty, hunger and exclusion.

Current statistics reveal that

10

percent of the population concentrates 42 percent of all

income, while

60

million Mexicans subsist in poverty.

According to ECLAC (the United Nations Economic

Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean),

four out of every 10 Mexican children are poor,

that’s a total of 4 million or 18 percent of all poor

children in Latin America.

And the situation is not any better in the field of

education. At a public ceremony commemorating the centennial

of the Revolution, José Narro Robles, president of

Mexico’s leading university, UNAM, gave some

alarming figures: “Today,

in

2010, there are 5.8 million people in Mexico who do not know

how to read and write, a number not very far below the 7.8

million illiterate persons that existed before the armed

movement.”

A hundred years ago the peasant movement was the architect

and main force behind the Revolution. Mexico’s powerful

groups have obviously neither forgotten nor forgiven that

“excess” and have been implementing an economic and social

model that excludes the peasant population and causes an

outrageous emptying of the countryside.

This exodus explains why

76

percent of the 105 million Mexicans who live in the cities

are just struggling to get by.

Of the population that remains in rural areas,

eight out of every ten persons lives in extreme poverty and

is barely surviving.

| |

|

| |

Despite increased spending in food imports,

14.42 million Mexicans were living in food

poverty in 2006, and by 2008 that figure had

shot up to 19.46 million. Recent data reveals

that 46 percent of the population suffers from

low to severe food insecurity.

(Carlos

Fernández-Vega,

La Jornada)

|

| |

|

There are less and less farmers, and those who do remain are

becoming increasingly poorer,

as reported by professor Víctor

Palacio Muñóz: “In 1991

nearly 58 percent of all small agricultural producers earned

a daily income that monthly amounted to less than a minimum

wage. In 2003 that percentage had increased to 77 percent,

and it is possible that it is now over 80 percent.”

“A basic food basket costs 2.46 monthly minimum wages,”

Muñóz said, illustrating the severity of the crisis that

affects rural families.

More hunger,

less sovereignty

…NAFTA, good ol’ NAFTA….

Land for the peasants / that’s the main goal / because only

they, gentlemen, / will use it to grow / Favor the community

/ above the individual owner / and always put / communal

rights first.

(“Corrido

de la Canción de Zapata Vivo,” Mexican folksong)

Mexico’s

food sovereignty has been severely eroded with the

advancement of neoliberalism and the signing of the

Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada

(NAFTA), which went into force in 1994.

If the food security of Pancho Villa’s and

Emiliano Zapata’s troops had depended on food imports as

Mexico does today to feed its population, the country

would not be celebrating 100 years of Revolution.

“At

present, Mexico’s countryside produces more migrants than it

does food and it exports more farmers than it does farm

products,”

Miguel Ángel Escalona1

sentences.

Food imports have grown steadily over the last ten years.

In

2004 Mexico imported 10 percent of the food it consumed; by

2006 it was importing 40 percent; and today it imports

almost 52 percent, and the tendency is for it to keep on

rising.

The birthplace of corn is importing about 33 percent of the

domestic demand for this cereal -some 600,000 tons a month-

and, as stated recently by the general secretary of the

National Confederation of Corn Producers of Mexico (CNPAMM),

Carlos Salazar,

“Due to domestic demand and the scarce support for national

production, in one year the country will have imported some

14 million tons of corn.”2

It also imports 75 percent of the rice it consumes, and

according to data from the National Peasant Confederation

(CNC), in the last three years beef imports have grown by

440 percent, poultry meat imports by 280 percent, and pork

by 210 percent.

| |

|

| |

From January to March 2010

Mexico - a country with over 10,000 kilometers

of coast - increased by nearly 50 percent its

imports of fresh and chilled fish.

|

| |

|

While Mexico has the highest per capita consumption of soft

drinks in the world, with an annual 112 liters per person,

its annual per capita consumption of milk is an average of

97 liters,

barely 50 percent of the amount recommended by the Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

But there is another problem here: the volume of milk

produced domestically is not enough to cover even that

demand and the country is forced to import about 190,000

tons.

Before NAFTA came on the scene, Mexico

exported sugar. Now the country not only imports nearly

600,000 tons of fructose, it also buys 250,000 of cane sugar

abroad.

More empty stomachs,

Less State

Poor Mexico, so close to the United States, so far from

bread

I’m leaving now, going to follow my destiny / I don’t want

to be a farmhand anymore / I’m taking the new path / blazed

by the Revolution / and if ever I come back, it’ll be as a

peasant / who won’t be working to fatten up any masters.

(“Nos

dejaron los olotes,” Revolutionary Corrido)

The results of a survey on the state of children and

adolescents in the context of the world financial crisis,

conducted in the second half of 2009 by the United Nations

Children’s Fund (Unicef)

and the National Council for the Assessment of Social

Development Policies (CONEVAL), would be enough to

merit another revolutionary uprising.

Carlos Fernández-Vega3

informs that that study found that “in just one year the

percentage of Mexican households affected by severe food

insecurity more than doubled, up from 8 percent in 2008 to

17 percent in 2009.”

The most dramatic change experienced from 2008 to 2009 was

in the percentage of homes that declared they had at least

one child who had eaten less than necessary, as this figure

jumped from 14 to 26 percent - that is, an increase of 86

percent over the period considered.

“One out of three households admitted they considered

buying cheaper or poorer quality food products as a way of

improving their home economy, and two out of three

households reported having resorted to that strategy in

2009,” Fernández-Vega notes.

According to data from the Central Bank of Mexico,

in the first 52 months of the administration of President

Felipe Calderón,

whose term will end in 2012,

the country squandered almost 43 billion US dollars buying

food abroad

-

that’s double what Calderón’s predecessor spent in a similar

period.

In March alone, a total of US$1.23 billion - or US$1.7

million an hour - were spent on food imports, primarily

milk, corn and wheat from the United States.

4

Mexico’s

National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEG)

reports that, in contrast, in that same month the country’s

dwindling agricultural activities contributed with only 3.5

percent of the national GDP.

Data from the political group Central Campesina Cardenista

reveals that Mexico currently imports 99 percent of

the powdered milk, 60 percent of the beef, 80 percent of the

rice, 90 percent of the oilseeds and 35 percent of the

sorghum it consumes.

If the trend continues -and it is expected to increase-, at

the end of President Calderón’s term

Mexico will have spent some US$70 billion in food imports.

This situation poses two resounding questions:

How many jobs would be created if this massive amount of

money were to be used to implement proper policies? How many

people would be able to live and produce decently in the

countryside? How many small and medium-sized food companies

would be developed? What kind of country would Mexico be

today?